Originally posted in BBC News on 06 December 2021

By Rupert Wingfield-Hayes

In a world racing to reduce pollution, Australia is a stark outlier.

It is one of the dirtiest countries per head of population and a massive global supplier of fossil fuels. Unusually for a rich nation, it also still burns coal for most of its electricity.

Australia’s 2030 emissions target – a 26% cut on 2005 levels – is half the US and UK benchmarks.

Canberra has also resisted joining the two-thirds of countries who have pledged net zero emissions by 2050.

And instead of phasing out coal – the worst fossil fuel – it’s committed to digging for more.

So it’s no surprise that Australia is being viewed as a “bad guy” going into the COP26 global climate talks in Glasgow, analysts say.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s government is under huge pressure to do more.

Loyalty to the industry

Mining has helped drive Australia’s economy for decades, and coal remains the country’s second-biggest export.

Only Indonesia sells more coal than Australia globally.

The government often credits coal for much of the country’s wealth, but many analysts argue this is overblown.

Coal exports totalled A$55bn (£29bn; $40bn) last year, but most of this wealth was kept by mining companies. Less than a tenth went to Australia directly – that’s about 1% of national revenue.

The coal workforce of 40,000 is about half the size of McDonald’s in Australia. But coal jobs do sustain some rural communities.

The mining sector has always wielded influence in Canberra.

Though most voters want tougher climate action, some coal towns lie in swing constituencies that are key to winning elections.

The mining lobby has “distorted” much policy over the years, says Prof Samantha Hepburn, a climate law expert at Deakin University.

The current government dismantled Australia’s emissions trading scheme in 2014, shortly after winning power in a campaign heavily backed by mining interests.

It’s never again tried to put a price on carbon, or to restrict emissions from fossil fuel producers.

Instead it’s provided extra support to coal. This includes:

- Approving new mines and extensions: There are over 80 proposed projects including plant upgrades

- Tax subsidies: About A$10bn went to fossil fuel companies last year alone

- ‘Clean coal’ investments: Schemes such as carbon capture and storage, often criticised as ineffective

Chasing a shrinking market

Australia argues coal will continue to generate national wealth for decades to come.

It talks up demand in Asia, particularly from industrialising economies.

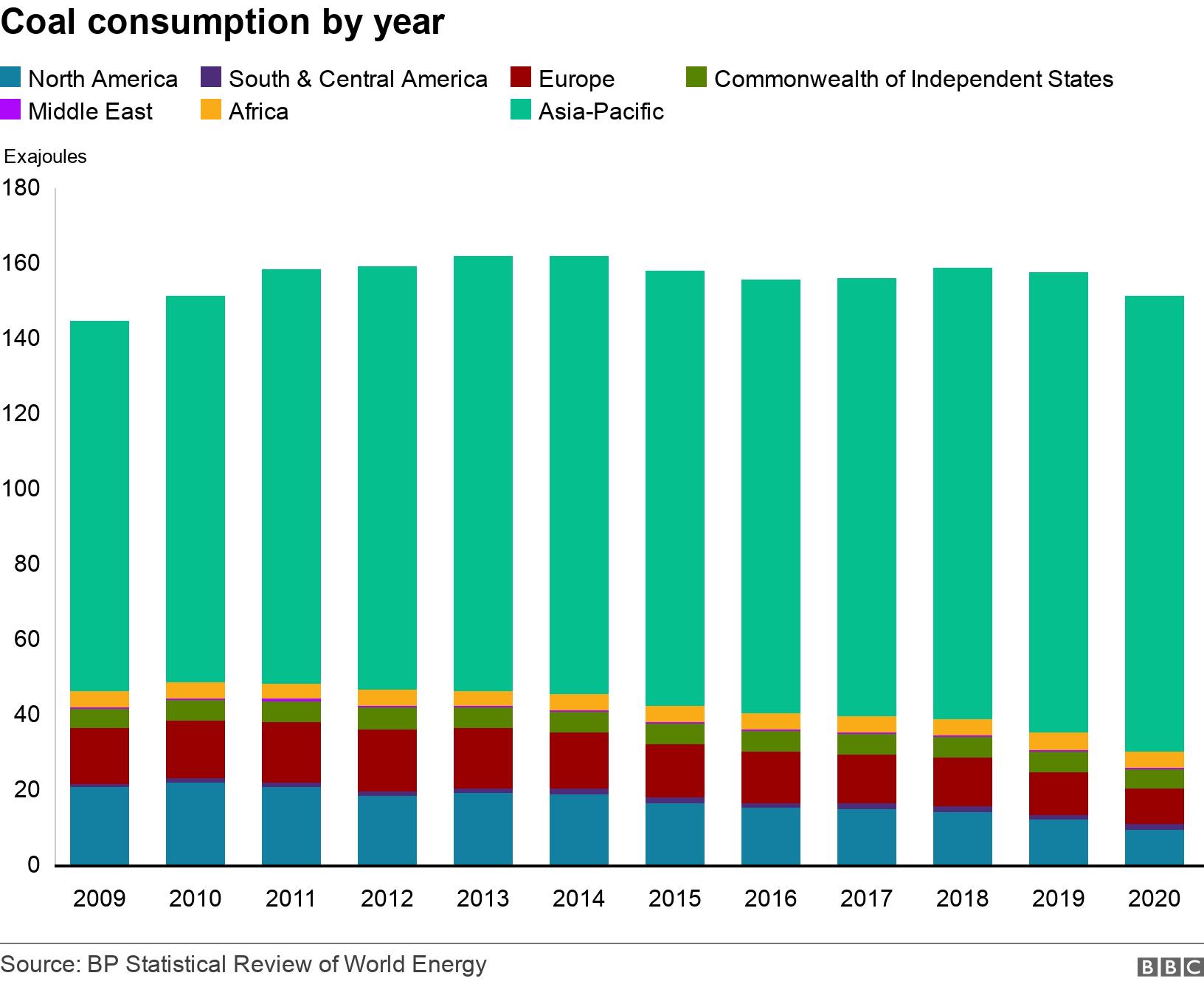

China and India alone account for 64% of global coal consumption. Demand in Indonesia and Vietnam has also surged.

But analysts say there’s no long-term market as countries race to meet emissions goals.

Australia’s biggest coal buyers – Japan, South Korea and China – have all pledged net zero targets by mid-century.

Coal use has already plunged in North America and Europe. The G7 rich nations and China, as well as many banks, have committed to stop financing overseas coal projects.

“Australia knows the party is over. But the police haven’t been called yet. So they’ll continue to party on until they’re stopped,” says Richie Merzian, a climate expert at the Australia Institute.

Missing the green opportunity?

Australia could end its literally toxic relationship with coal fairly quickly, experts say.

Its economy is stable and well-diversified to absorb the loss of coal exports.

But Australia controversially sees liquefied natural gas – another dirty fuel – as its next big domestic energy source.

The government has already pledged half a billion dollars to new gas basins and plants, defying global calls for an end to new fossil fuel projects.

This has frustrated those who say Australia should be investing to become a renewables superpower.

As one of the sunniest and windiest continents on Earth, Australia is “uniquely placed to benefit economically” from its abundant natural resources, says the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an intergovernmental organisation.

Its industries are also well positioned to pivot to new export markets like green steel and aluminium.

Advocates say coal workers could instead mine for the rare minerals needed for batteries and magnets that will power renewable energy grids.

Canberra has put some money into renewables, but the majority has come from state governments and businesses.

Its allegiance to fossil fuels has scuppered progress, critics say.

The government has cut its renewables spending in recent years, and there is no current national clean energy target.

It has also withdrawn from the UN’s Green Climate Fund, and tried to change one local fund’s mandate so taxpayer money could go to coal projects instead.

“The rest of the world is accelerating past coal,” says the Climate Council, a group of scientists.

“Australia can either choose to reap the opportunities of this transition, or be left poorer and less secure.”