Originally posted in The Daily Star on 04 March 2022

On February 22, 2022, during a meeting of the Executive Committee of the National Council (Ecnec), the prime minister instructed the relevant government agencies to gradually cut down on subsidies supporting economic activities of the country. She specifically mentioned stopping subsidies to the power and energy sectors in Bangladesh. The directive comes at a time when the finance ministry has been struggling to accommodate the exorbitant demand for subsidy payment for 2021-22 fiscal year (FY), due to the rise in the prices of petroleum and liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the global market. According to news reports, the demand for subsidies in different sectors has outweighed the budget allocation for FY22: about 135 percent of additional budget allocation (Tk 11,500 crore) is required for the power sector, 525 percent (Tk 21,000 crore) to import LNG, and about 194 percent (Tk 18,500 crore) to produce fertilisers using natural gas.

No doubt, the prime minister’s directive is aimed at reducing the fiscal pressure on the public exchequer to cover the import and other incentive-based payments. However, her directive indicates a medium- to long-term perspective on revising subsidy-related activities. Therefore, we welcome the prime minister’s directive on the gradual withdrawal of subsidy, particularly from the power and energy sectors.

Implementing the directive requires a number of short-, medium- and long-term impacts and implications for the power and energy sectors to be considered. In the absence of subsidy, the immediate implication would be faced by the Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB) and Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation (BPC), two leading agencies in the power and energy sectors—how they would realise their additional financial burden due to a rise in petroleum and LNG prices.

The medium-term implication would include how the BPDB and BPC would undertake a drastic reduction of operational costs and thereby come out with a gradual reduction of operation losses—particularly for the BPDB, which has been operating at a loss for years. The long-term implication would be how the power and energy sectors would take this directive as an opportunity to gradually reduce the burden of fossil-fuel-based energy mix and gear towards renewables. In fact, the prime minister, immediately before COP26 last year, wrote in the UK-based daily the Financial Times about achieving the target of meeting 30 percent of the total energy requirement in Bangladesh with clean power by 2030.

The impacts and implications of subsidy withdrawal in the power and energy sectors are largely linked with the state of BPDB and BPC’s financial conditions. According to their annual reports in 2021, the state-run organisations are in an about-face where their operating incomes are concerned. BPDB’s net operating income has been in red over the last several years—even after receiving subsidies. In 2021, BPDB incurred a loss of net income (–Tk 8,665 crore), which was 99 percent higher than that of 2020 (–Tk 4,351.7 crore). Meanwhile, BPC’s operating income has been green over the years. In 2021, its net operating income was Tk 6,593.7 crore, which increased by 30.2 percent from that in 2020 (Tk 5,065.3 crore). However, due to a rise in energy prices during FY22, the financial balances of BPDB and BPC have weakened significantly, and will be in the red, which will be better understood after the end of this fiscal year (June 2022). Against such a backdrop, both the organisations’ subsidy issues need to be considered.

Over the last decade, the BPDB has received a significant amount of subsidy: a total of Tk 71,466 crore between 2010 and 2021—Tk 5,956 crore per year, on average. The amount of subsidy increased every year. On the other hand, the BPC received a subsidy of Tk 30,086 crore between 2010 and 2015, and from 2016, it did not take any subsidy from the government as it was making profits.

Subsidising the power sector is different from subsidising the energy sector. Across the power and energy sector value chains, subsidies are used in many channels. In the case of primary energy, subsidies are provided to the power generation companies to supply fuel (petroleum and LNG) at reduced prices. The power tariff offered to end consumers is administered by the government—reviewed and suggested by the Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission (BERC). These administered prices are lower than the generation cost, which is complemented by a considerable amount of subsidy. Apart from that, the BPDB pays capacity charges to the private power producers—independent power producers (IPPs) and quick rentals—if the minimum amount of electricity is not acquired from them. At present, more than 50 percent of BPDB’s operating expenses are the capacity charges that it has to pay. These charges are a major reason behind the high subsidy requirement of BPDB.

The private power generation companies enjoy other forms of subsidies, such as long-term tax breaks, duty waivers at the import stage, and lower rates of corporate taxes. Similar tax breaks are also provided to renewable energy-based power producers.

Overall, subsidy reduction should take into cognisance both direct and indirect forms of subsidies used in the power and energy supply chains. Hence, these different forms of subsidies and the means to address them across the value chains need to be identified.

To reduce the financial pressure in recent months, both BPDB and BPC need short-term solutions. A possible option would be to take loans from international development banks or bilateral development partners. The government took a loan of USD 25 million in 2007 under import payment financing from the Islamic Development Bank. In 2018, it planned to borrow USD 1 billion from the same bank for the same purpose. Taking such loans to address sudden and transitory situations would be the right option.

Another option could be to put pressure on different public, semi-government and private entities to pay their massive dues to these two organisations; as of 2021, the amount that BPDB was owed stood at a staggering Tk 9,000 crore. Collection of these dues in the shortest possible time would reduce the financial pressure on both the organisations. Besides, the government should not take the available surplus fund from these organisations that they could use to meet their expenses.

We strongly oppose the adjustment of power and energy tariffs at the retail level to accommodate the temporary financial burden on BPDB and BPC. Any kind of tariff adjustment would be a long-term burden on the end consumers, further intensifying the inflationary pressure on them.

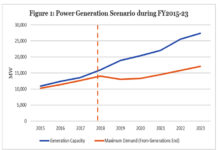

In the wake of subsidy withdrawal, the BPDB needs to look into improving its operational efficiency in power generation and withdrawing from the obligation of paying capacity charges to the IPPs for the medium term. The power sector abounds with surplus generation capacity, which is as high as 59 percent as of February 26, 2022. First, the BPDB should not approve the extension of the quick rental power plants’ contracts after completing their current terms (most scheduled to end in 2023 or 2024). Second, old, dated and inefficient power plants (mostly under the public sector) should be shut down. Third, the BPDB should consider discontinuing power plants using expensive fuels.

Fourth, it should offer a new contractual arrangement to the IPPs by replacing the clause of obligatory capacity charges with the “no electricity, no payment” clause. This has been applied to a number of power plants recently approved for extension. In fact, this “no electricity, no payment” clause should be considered for all new contracts. Such measures would help reduce the financial burden on the BPDB. Finally, the BPDB should focus on improving efficiency throughout the power supply chain—generation, transmission, and distribution.

Similarly, the BPC should not promote LNG-based energy systems in the country; it should pursue respective ministries and departments as well as the private sector stakeholders about shifting the focus towards alternative energy options. Sectors such as transport, industry, and agriculture have ample scopes for going to alternate energy mix based on renewables, such as rooftop solar photovoltaics (pv) technology in the industries, battery-based transportation, solar power-based irrigation, etc.

Withdrawing subsidies in the medium-to-long term would create opportunities for a market-based system in both power and energy sectors. A subsidy reduction under a comprehensive market-based system, with special focus on reducing fossil-fuel-based power generation, would help reduce the cost of sourcing power from fossil-fuel-run power plants only. This would require the withdrawal of fiscal benefits provided to IPPs and quick rentals in the forms of tax breaks, waiver from VAT and other duties, etc. Such a measure would create space for renewable-energy-based power generation in Bangladesh. This process would be further promoted if the government considered a “positive discrimination” in favour of clean energy, by providing a special subsidy to renewable energy-based power producers, which could attract more local and foreign investments to the country.

In the BPC’s case, it should focus on exploring local gas reserves more, instead of importing the costly LNG. There are several options in exploring local gas reserves: (a) Discovery of gas fields to increase the reserve base; (b) Field development with an increasing number of development wells per field; (c) Resume production at stranded gas reserves; (d) Optimise the production wells; (e) Work over the dried-up production wells; and (f) Recover unconventional reserves.

One of the challenges of subsidy cutdown would be implementing the alternative measures efficiently. Any unwanted situation due to subsidy withdrawal should not become a burden on the end consumers. The required measures need to be undertaken with the cooperation of the private sector—particularly the IPPs. This also requires accommodating their concerns, if any. At the same time, the government should be bold enough to resist any unnecessary pressure from the vested quarters. A gradual and efficient way of implementing subsidy phase-out would help us develop a market-based system that would create better scopes for clean energy and clean power systems in the country in the long run.

Dr Khondaker Golam Moazzem is research director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).